How loud is music, actually?

- Dr. Teresa Wenhart

- Sep 23, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 30, 2025

According to the WHO, 50% of individuals aged 18-34 are at risk of noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL). The risk of NIHL is not only dependent on the volume but also on the daily duration of exposure to sound. Many professional musicians exceed legal noise exposure limits through their daily practice, especially when performing in ensembles, bands, or symphony orchestras.

Volume and Sound Intensity

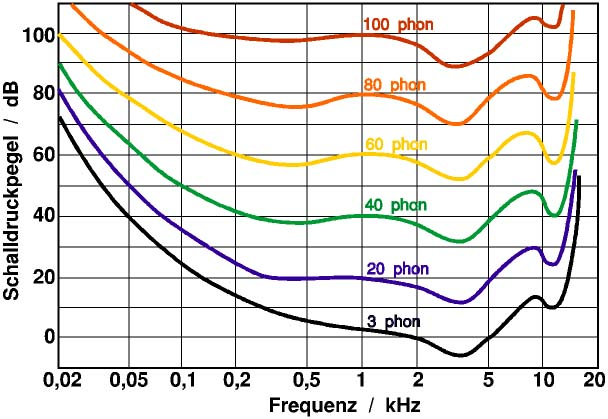

How loud is music, actually? Each instrument has its own sound intensity, which can be measured in decibels (dB). Decibel is a logarithmic unit that measures the relative difference between two volumes. An increase of 3dB corresponds to roughly a doubling of sound intensity, meaning if two cellos are each playing at a sound intensity of 80dB, the total sound intensity is 83dB. Perceived volume is a psychoacoustic measure, measured in "phon," and is dependent on frequency. Doubling sound intensity does not correspond to a doubling of perceived volume psychoacoustically. The human ear's perception of volume follows what are called isophones, which are curves that indicate equal loudness at different frequencies and sound intensities. In low frequencies, people require significantly higher levels to perceive them as equally loud as high frequencies.

Figure: Isophones are contour lines of equal loudness in human perception.

For instance, a tone at 1 kHz (approximately a C5) is perceived at the same loudness level at a sound pressure level (SPL) of 80 dB as a tone at 60 Hz (a deep Cello C), which is slightly over 90 dB SPL. However, the level of the low-frequency tone is already more than 8 times higher because each increase of 3 dB SPL corresponds to a doubling of sound intensity. High frequencies are perceived as too loud or painfully loud earlier than low frequencies, partly due to this psychoacoustic characteristic of hearing. The timbre (e.g., how shrill a sound is) also plays a role in how unpleasant and loud a tone is perceived. People tend to underestimate the loudness, especially in the low-frequency range.

This psychoacoustic loudness, evident in the isophones, is taken into account in the A-weighting of sound intensity, dB(A), which is often used in noise level measurements for noise control purposes.

How loud is too loud?

Most countries' noise protection regulations are quite similar. Both the German Social Accident Insurance (DGUV) and the Swiss Accident Insurance Fund (SUVA) specify a limit of 85 dB(A) as the continuous sound level for a 40-hour workweek, along with a peak level of 137 dB(C). Above this threshold, employers are required to implement noise protection measures.

By adhering to this harmful sound exposure limit of <85 dB(A) for a maximum of 8 hours a day, one can derive how much shorter the maximum working time must be at higher sound levels. For every 3 dB(A) increase in the average level, the recommended maximum exposure time is halved, as sound intensity doubles. This means:

<85 dB(A): maximum 8 hours a day

<88 dB(A): maximum 4 hours a day

<91 dB(A): maximum 2 hours a day

<93 dB(A): maximum 1 hour a day

<95 dB(A): maximum 30 minutes a day

<98 dB(A): maximum 15 minutes a day

Depending on how loud one's instrument is and how frequently and for how long one plays in larger orchestras, musicians should proactively use hearing protection to reduce sound intensity. Hearing protection not only reduces the risk from sudden or short-term very loud sounds but also extends the maximum exposure time accordingly.

See also: 'Hearing Protection for Musicians' and 'Top 5 Myths About Hearing Protection for Musicians'.

How loud is music, actually?

Classical music, especially in larger ensembles like orchestras, with loud instruments (percussion, brass, etc.) and in small venues, can often reach peak levels of 120-135 dB(A). Even if it's not extremely loud throughout the entire rehearsal or performance, the average levels frequently exceed legal limits when considering the duration of the work hours. A comprehensive study conducted by the Freiburg University of Music in 2011 measured sound levels using microphones placed close to the ears of musicians during a rehearsal of the university orchestra performing romantic repertoire. The measurements resulted in an average exposure (continuous sound level) ranging from 85.5 to 93.9 dB(A) depending on the instrument group, exceeding legal limits at nearly all measurement points when taking the duration of sound exposure into account. Depending on the study, orchestral musicians are often exposed to an average level of around 90 dB(A).

Volumes of Individual Musical Instruments

The sound pressure level of musical instruments can vary depending on the type of instrument, playing technique, distance to the instrument, and the environment. Here is a rough overview of estimated sound pressure levels for various musical instruments:

Acoustic Guitar: 70-90 dB

Piano (acoustic): 60-70 dB, Grand Piano: 70-80 dB

Violin: 82-93 dB, about 3-6 dB more on the left ear than the right ear

Cello: 85-110 dB

Double Bass: 90-105 dB

Flute: 85-115 dB, significantly higher load on the left ear than the right ear

Clarinet: 85-114 dB

Trumpet: 90-130 dB

Saxophone: 85-115 dB

Drum Set: 90 to >140 dB

Electronic Instruments: Depending on amplification, >120 dB"

Please note that these are rough estimates and can vary widely depending on the specific instrument, player, and playing conditions.

For comparison, here are typical sound intensities of everyday noises:

Whispering: approximately 20 dB

Raindrops: 50-60 dB

Birdsong: 40-70 dB

Normal conversation: about 60-70 dB

Full restaurant: 70-80 dB

Inner-city traffic: 70-85 dB

Train or subway: 85-100 dB

Rock concert: 110 to >140 dB

Protecting one's hearing in daily life, especially during commuting and travel, is crucial for musicians as well.

See also: 'Hearing Protection for Musicians' and 'Top 5 Myths About Hearing Protection for Musicians'.

Sources and further reading

Altenmüller, E., & Klöppel, R. (2015). Die Kunst des Musizierens: von den physiologischen und psychologischen Grundlagen zur Praxis. Schott Music

Richter, B., Zander, M., Hohmann, B., & Spahn, C. (2011). Gehörschutz bei Musikern. HNO, 59(6), 538-546.

Comments